Interview conducted by Melissa L. Michaels, Capiche Contributor/Strategic Partner, Michaels & Michaels Creative, LLC

Having founded iOpener Institute for People & Performance in 2003, Happiness at Work author Jessica Pryce-Jones led this pioneering organization until leaving the company to embark on her current adventure in 2017. Today, she is the founder and director of Webpsyched, a collective that integrates hard data, soft data, and intuitive data along with the team’s diverse, deep expertise to help organizations and individuals achieve greatness. Webpsyched clientele range from health care multinationals to banks to manufacturing and fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) industries to educational institutions to nonprofits to government agencies to creative, publishing, and engineering companies. A fellow of Harvard’s Institute of Coaching, Jessica has taught at such business schools as Cambridge Judge, Cass, Cornell, Chicago Booth, Cranfield, London Business School, and Saïd (Oxford).

Q: iOpener Institute was a trailblazer in the field of organizational development. What was different about iOpener’s services at the time you founded it, and how did companies respond to this new approach?

A: What was different was that we provided tools to measure and base an intervention on and then the interventions themselves as part of that solution. So, consultants had access to a one-stop-shop of tried and tested individual and team development activities without needing to reinvent the wheel each time. That meant we quite quickly built a global community of practice.

Q: Can you give a couple examples of major organizations that benefited from iOpener Institute’s services and explain what those benefits entailed?

A: We did a lot of work at one stage with Domino’s Pizza, and that was all about engagement and looking at exactly what was going on in all the different teams and across all the different layers up and down, then devising some interventions that would help senior leaders and individuals as well. That was really exciting to do. Another thing we did was partner with The Wall Street Journal to see what we could do with the research. We got a lot of data and insights at the time.

Q: You mentored Chris Cook while she was completing her master in management (MiM) thesis on the science of happiness at work in 2010–11, right after your industry-defining book, Happiness at Work: Maximizing Your Psychological Capital for Success, was published. Chris got so excited about the research, it changed her career path and expanded her focus from marketing to defining and then actually living your brand. Can you speak to your experience of mentoring Chris and your subsequent work with her as the only person in the Northwest accredited by iOpener Institute?

A: It was fun to mentor Chris because she’s up for all of it, she’s open to all of it, and she’s very thoughtful. The thing I like about working with Chris is her thoughtfulness and her willingness to get deep, and not everybody wants to do that, wants to really introspect on stuff and get to grips with it—that’s what’s special about Chris’s approach.

A: It was fun to mentor Chris because she’s up for all of it, she’s open to all of it, and she’s very thoughtful. The thing I like about working with Chris is her thoughtfulness and her willingness to get deep, and not everybody wants to do that, wants to really introspect on stuff and get to grips with it—that’s what’s special about Chris’s approach.

Q: What strengths does Chris bring to organizational development and coaching?

A: The special strength that Chris brings both to organizational development and coaching is that ability to go deep and to do that pretty quickly. And you can see when she’s thinking, and that’s a lovely thing to watch.

Q: It’s been two decades since you founded iOpener and wrote Happiness at Work. How has the science of happiness at work field evolved during that time?

A: Now it’s no longer a dirty word to say “science of happiness at work” and ask people if they’re happy. I think a lot of that is the next generation is moving on. When I first started talking about happiness at work, I’d go into a conference, and people would say, “I can’t talk about that. I can talk about engagement or fulfillment or satisfaction, but happiness, no.”

A: Now it’s no longer a dirty word to say “science of happiness at work” and ask people if they’re happy. I think a lot of that is the next generation is moving on. When I first started talking about happiness at work, I’d go into a conference, and people would say, “I can’t talk about that. I can talk about engagement or fulfillment or satisfaction, but happiness, no.”

Everybody has recognized that it’s for all now. There are plenty of researchers in the field, and that’s a joy. You don’t want to be alone surfing on a wave because that tells you there’s probably a lot of coral and rocks underneath the surface.

Q: Since leaving iOpener, you’ve started a new venture related to intuition. What services does Webpsyched provide, and why was iOpener a perfect springboard for this endeavor?

A: With iOpener, I always thought there was something deeper. I remember when the book came out saying to some of my business partners and associates, “There’s something beyond this,” and they’re going, “No, no, Jess, this is enough.”

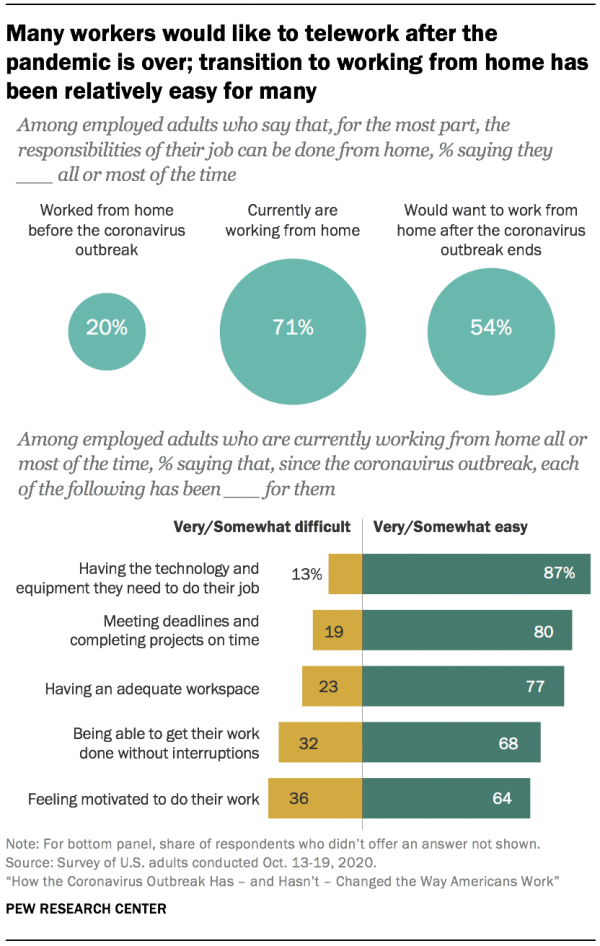

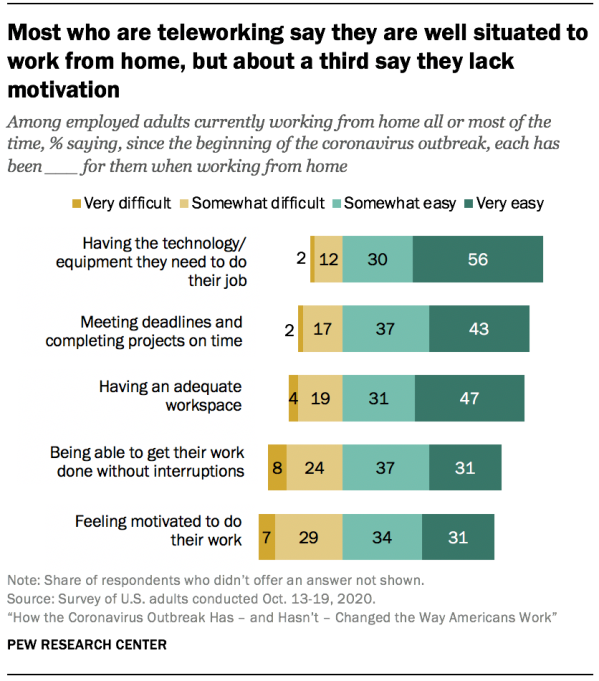

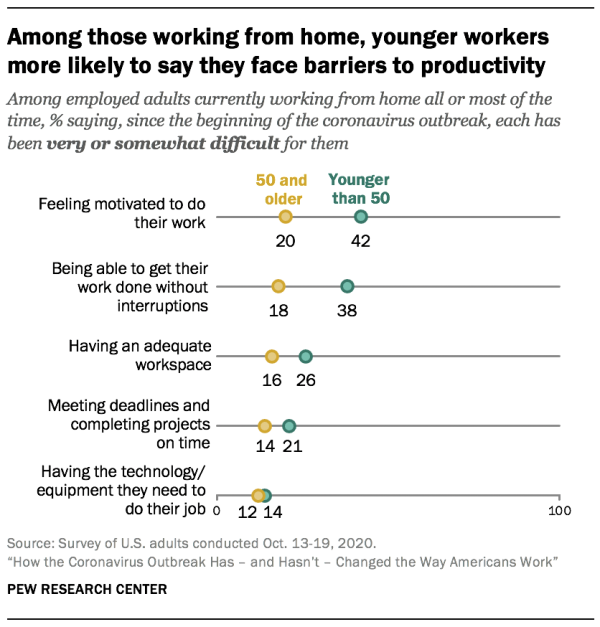

With this new venture related to intuition, the services are the same as iOpener’s, but we wanted to take it to the kind of level where Chris goes—a deeper level. And it’s all on the web. We’ve all discovered with COVID that we can work remotely, and it’s easy. It’s not the same as a face-to-face experience, but it does deliver close to the experience in a different way.

We’re doing organizational development, organizational health checks, senior team coaching, consulting projects, and some workshops. iOpener had become a little bit top-heavy, and this is super-lean. I really like working in a very lean kind of way, which I think is a bit more modern.

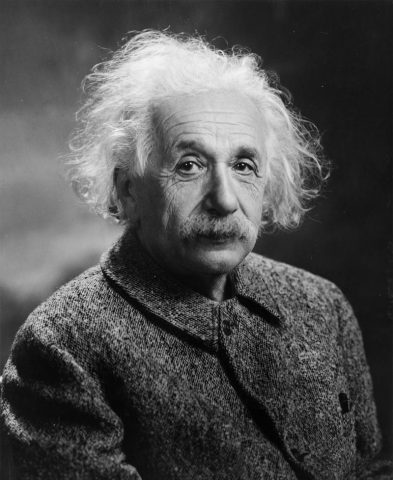

Q: You open your article Using Your Intuition with a quote by Albert Einstein, “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” How does Webpsyched help organizations and individuals rediscover that gift?

A: We put together some workshops to show people how you use this skill. All leaders say they make decisions using their intuition, and people want leaders to. When did you last buy a house or pick a partner using a cost-benefit analysis? With all of our big decisions where we have either too much information or zero information, we have to use some kind of inner sense. Whether you call it your intuition, your judgment, or your experience, we use that information to make our decisions, but we don’t talk about it.

In the same way that talking about happiness is now an easy thing, I’d like to be able to bring using, talking about, and understanding how you use your intuition to the workplace to that point.

At the workshops, we just talk about it. We ask people to go with their gut feeling, what their heart’s telling them. Because if we don’t talk about it, how do we ever surface this thing? And if we don’t hear and share how other people use it, ditto.

Q: Also in that article, you share a striking (no pun intended) example of how intuition saved you and your unborn child from injury when a ball crashed through a window. You write:

“During break, I went to the staff room to get a cup of coffee. I stood drinking it by a large glass window, watching the kids playing football in the playground. As I stood there, the thought came to me ‘a kid is going to kick that football in this direction; it will come through the window, I’ll be hit by the ball, showered in glass, and my face will get cut.’ And having had that thought, I started to take a couple of steps back.

“I’d moved about three paces when the football came crashing through came window to land near my feet; sure, a few glass shards were sprinkled on my bump and I had a tiny scratch on one cheek. But that was all. As teachers rushed up to me to see if I was OK, they commented on how calm I was. I was totally unruffled because I’d known it was going to happen.”

Q: Can you talk about other times when you intuited and subsequently averted danger?

A: Actually, the very first time I used my intuition, I remember I was four, and my mother asked me to jump over a little wooden stile. I didn’t want to jump, and she was encouraging me, “Yeah, Jess, jump, jump, jump!” I just knew that something bad was going to happen, and I was only four.

As I hit the ground, I half-bit my tongue off, and I was bleeding everywhere. It’s very sharp in my memory, but I remember so strongly not wanting to do it and then doing it. And we’ve all had that experience of not wanting to do something, not listening to our intuition, going ahead, and it’s been a mistake. That was the very first time I was aware of it, but I’ve used it countless times since then. I’ve known when cars were coming around a short bend, I’ve known when a higher-up wasn’t going to be good, I’ve known when I’ve taken the wrong job. But when I was young, I still took the wrong job. I remember walking up the steps going, “This is the wrong job. What am I doing?”—before I’d even gone in there. I was young and foolish.

I had a breast cancer experience, and I saw two separate events. One was me walking into my house and sticking the key in the door and being terribly upset and alone in my home. And the second was just getting a really strong sense that I needed to go for an unscheduled mammogram. And I didn’t pick up that the two were related, which is probably a good thing, but I went and had the unscheduled mammogram, and they did find breast cancer. If I had waited even a few more months, it would have been a very bad outcome for me, but, actually, it’s been a super outcome, so thank you, my intuition.

Q: There has been an explosion of research on the gut microbiome—some call it our “second brain” or a “gut feeling”—over the past decade. Scientists have discovered our gut takes in thousands of details at lightning speed, and those who are attuned to their intuition and emotions can benefit from that data, whereas those ruled by their rational mind often override their gut instinct to their detriment. How can people cultivate their second brain for the betterment of their lives and organizations?

A: On the explosion of research and the gut biome, your second brain—and also heart—what do they say? In your gut, you carry the same amount of neurons in your gut as in your brain. It’s your gut mind, you get that instant feeling that in your stomach that you should or shouldn’t do something. Same with your heart.

How do you cultivate that? Keep a journal, write down when you’re intuiting something and what your stomach, what your heart, is telling you—or any other part of your body, because it doesn’t have to just be your gut and your heart.

I’ve been working with a delightful person, and he often says to me, “What are your knees telling you?” You can use any part of your body. Quite often, it’s good to use a part that you don’t always use because you don’t make the same assumptions. Write it down. When you make these judgments, write it down because then you can see when you’re right and when you’re not right. Who’s going to walk into the elevator first? Whose email is going to be top of your list? What’s someone going to say in a meeting? Who’s going to speak next? These are very simple ways of tuning in to how you use your intuition.

Q: In his book No Self, No Problem: How Neuropsychology Is Catching Up to Buddhism, cognitive neuropsychology PhD Chris Niebauer uses the left brain/right brain paradigm to describe what is fundamentally the difference between the categorical mind and the intuitive mind, which also maps closely to Western philosophy versus Eastern philosophy. Although the left-right division has fallen into disuse by neuropsychologists, Niebauer uses this simplified model to help us understand the distinction between two modes of being, noting, “the left brain is the language center and the right brain is the spatial center.” He explains:

“In the same way that the left brain is categorical, the right brain takes a more global approach to what it perceives. Rather than dividing things into categories and making judgments that separate the world, the right brain gives attention to the whole scene and processes the world as a continuum. Whereas the attention of the left brain is focused and narrow, the right brain is broad, vigilant, and attends to the big picture. Whereas the left brain focuses on the local elements, the right brain processes the global form that the elements create. The left brain is sequential, separating time into ‘before that’ or ‘after this,’ while the right brain is focused on the immediacy of the present moment.

Does this description of the right brain jibe with your findings on intuition? When your Webpsyched team is providing executive and personal coaching, how do your clients respond to the transition from left to right brain living?

A: The left–right brain paradigm, and the model there—I see that as a metaphor. And metaphors are a very good way of also using your intuition. What’s that like? And the brain will throw up some very powerful metaphors, which is a part of what I consider the intuitive experience.

The left–right brain doesn’t really sit well with me. Your brain doesn’t really work like that, but I do think that we, as a society, rely on rational judgment way too much. We talk about it way too much. And we don’t talk about this other experience that people have and use all the time, and that is the important thing.

The physical operation of it or how you perceive it doesn’t really matter for me rather than the doing of it. Any leaders who read this who are interested in talking to me, I would love to talk to them because I’m interviewing. I think the interesting thing is understanding and shedding light on other people’s experiences so we can have a conversation around this. Anybody who has had a very profound experience using their intuition and doing that at work, I would love to talk to you, so please do get in touch.

Q: Tell me about the Webpsyched leadership masterclasses. What is involved in these remote and face-to-face workshops?

A: I ask participants, “What’s your intuition telling you? What’s your judgment telling you? What are you thinking about this? And then what are you thinking?” Sometimes you can’t get to the intuition straight away, and sometimes our first intuitions are wrong. I think you need to get yourself to quite a grounded place to have those insights. When you’re rushing and hurrying, it’s harder to pay attention because intuition is also about paying attention, and you don’t pay attention when you’re in overload. That’s the important thing—to take yourself down to a place where you’re feeling connected with yourself so you can start listening to those signals because otherwise you miss them. I perceive them more as whispers—what are you whispering to yourself?

A: I ask participants, “What’s your intuition telling you? What’s your judgment telling you? What are you thinking about this? And then what are you thinking?” Sometimes you can’t get to the intuition straight away, and sometimes our first intuitions are wrong. I think you need to get yourself to quite a grounded place to have those insights. When you’re rushing and hurrying, it’s harder to pay attention because intuition is also about paying attention, and you don’t pay attention when you’re in overload. That’s the important thing—to take yourself down to a place where you’re feeling connected with yourself so you can start listening to those signals because otherwise you miss them. I perceive them more as whispers—what are you whispering to yourself?

Another way of using your intuition is to talk to it as if it was a person sitting in front of you and saying, “Oh, hello, intuition, what have you got to tell me today about this thing?” And listen for the answer. Then you can check in with yourself because you may not be right, not all intuitions are right, just in the same ways not all decisions are right. That’s when we second-guess ourselves and go, “Oh, it wasn’t working then,” and then we mistrust ourselves. It’s to build the trust in your experience and in you.

For the website leadership master classes, like everybody else, we’ve all been working on Zoom, and I am now running everything programmatically. People spend an hour, an hour-and-a-half, two hours max, and we do something as a program. And I much prefer that than a one-and-you’re-done. When it’s one-and-you’re-done, it’s more tempting to be the sage on the stage—sorry, all these rhymes—but actually, in a program, everybody is everybody else’s guide by the side. And that’s where you get some profound learning, because it’s the continuity, it’s the building of something.

I use a WhatsApp group so we’re in touch and giving people nudges and putting information up through that and adding readings or poems or videos—just little nudges to help people and offer reminders because building new habits is hard, as we all know, and building muscle is really hard. This is the equivalent of going to your mental gym.

Q: Why should values matter to an organization?

A: Because they are how people live the culture. Mostly, people say one thing and do another, but it’s how you can hold people to account. Values are extremely important in creating an organizational culture and then holding people accountable to make that culture live.

At Webpsyched, we’ve learned from our research and experience that when values are clear, communicated, and regularly reinforced, there is greater performance, happiness, commitment, satisfaction, and motivation. There’s also less anxiety and work stress. Value congruence helps with:

- getting support to drive change

- reducing unethical practices

- promoting positive work behavior

- encouraging people to participate in challenging activities

- instilling a greater sense of accomplishment

Q: You also write about resilience. I found your reference to Glen Elder’s discovery that “children who’d grown up in the Depression were much more resilient than people who’d faced their first challenge later in life” fascinating. In The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt documents the flip side of the equation in which helicopter/bulldozer parenting has yielded fragility instead of resilience, dependency instead of independence. How can parents build resilience in their children without subjecting them to harsh experiences and undue risks?

A: The question is what’s a harsh experience and what are undue risks. Of course, it’s going to be context- and person- or child-specific. You always want to give someone a test that is going to stretch them, going to get them out of their comfort zone. Always staying in your comfort zone never stretches it and gets you any further, but children are their own natural-born scientists. They will take risks, especially when testosterone kicks in and they start hanging out in groups, so I guess it’s got to be age-dependent as well.

This helicopter-tiger-bulldozer parenting hasn’t helped. I was talking to a Gen Z, and he was saying that the education experiences that he’s had means it’s impossible for him to listen to his intuition. He’s been taught that there are “answers” rather than that there’s a range of answers, so he has no clue how to listen in.

By our education system saying, “These are answers that are correct,” students are stressed about getting the correct answer. When you’re working with clients and in business, there are no correct answers. There are some answers that are better than others.

Regarding parents building resilience—let kids go exploring. Give them boundaries. Let them operate within those boundaries and constantly ask yourself, “Are these boundaries appropriate to my child?” If everybody else has got an iPhone, you probably want to give your child one, too. If all other kids are using WhatsApp, you probably want to allow them to do that, too.

I think things are very different today. When I was a kid, I was allowed to take the London Tube to school. My nephews are not allowed to do some of those things. Are we holding our children back by not allowing them to fall out of trees and break their arms? Maybe we are, because you could also discover that you can have a bad experience, get through it, and the world doesn’t end. And you need to discover that young. It’s no good discovering that for the first time in your forties because then it’s much harder to learn. It’s much easier to learn resilience younger.

Q: That also makes me think of an article called Thinking About Thinking I read back in the 1990s. The authors, Alan Carter and Colston Sanger, describe two modes of thinking they call mapping versus packing. Mappers are constantly mapping knowledge from one domain to another, building a coherent mental map of the world that enables them to achieve elegant solutions with fluidity and speed. Packers horde “knowledge packets” and must laboriously assemble them to produce mediocre results. The authors describe how mapping capabilities can be “reawakened by trauma,” citing the extraordinary transformation of Japanese manufacturing following World War II (i.e., Hiroshima and Nagasaki) from “an odd mix of the medieval and industrial ages” to a world leader in manufacturing within a generation. Your article What One Attribute Do You Need in a Robotized Workplace? seems to be describing the qualities of mappers. Do you have any suggestions on how packers can rewire their brains to become more like mappers?

A: Packers horde knowledge packets, yeah! As for how packers can rewire their brains, it’s going to take some mentoring. I talk about field tests. What’s a field test you can do? It’s not saying, “I’m going to change this forever,” but it’s a field test. And maybe it’s the same about resilience. What’s a field test that you feel you can let your children do, for example, and then you can reflect on that experience together. I’m not sure that it’s rewiring, but it’s giving yourself the confidence that what you’re doing is the right thing. One field test leads to another, and if you’re mentoring somebody or coaching them, I think that is probably the best way to go about it.

A: “And what else?” “And what else” is my favorite coaching question because it always leads to something else and to something deeper. If I had to take one in my back pocket with me, it would be that one.

A: It was fun to mentor Chris because she’s up for all of it, she’s open to all of it, and she’s very thoughtful. The thing I like about working with Chris is her thoughtfulness and her willingness to get deep, and not everybody wants to do that, wants to really introspect on stuff and get to grips with it—that’s what’s special about Chris’s approach.

A: It was fun to mentor Chris because she’s up for all of it, she’s open to all of it, and she’s very thoughtful. The thing I like about working with Chris is her thoughtfulness and her willingness to get deep, and not everybody wants to do that, wants to really introspect on stuff and get to grips with it—that’s what’s special about Chris’s approach.

A: I ask participants, “What’s your intuition telling you? What’s your judgment telling you? What are you thinking about this? And then what are you thinking?” Sometimes you can’t get to the intuition straight away, and sometimes our first intuitions are wrong. I think you need to get yourself to quite a grounded place to have those insights. When you’re rushing and hurrying, it’s harder to pay attention because intuition is also about paying attention, and you don’t pay attention when you’re in overload. That’s the important thing—to take yourself down to a place where you’re feeling connected with yourself so you can start listening to those signals because otherwise you miss them. I perceive them more as whispers—what are you whispering to yourself?

A: I ask participants, “What’s your intuition telling you? What’s your judgment telling you? What are you thinking about this? And then what are you thinking?” Sometimes you can’t get to the intuition straight away, and sometimes our first intuitions are wrong. I think you need to get yourself to quite a grounded place to have those insights. When you’re rushing and hurrying, it’s harder to pay attention because intuition is also about paying attention, and you don’t pay attention when you’re in overload. That’s the important thing—to take yourself down to a place where you’re feeling connected with yourself so you can start listening to those signals because otherwise you miss them. I perceive them more as whispers—what are you whispering to yourself?

The other way we were able to help get resources back to the fire victims was through our new Round Up Program called Change for Good. We quickly communicated to our community about the need to support displaced families and how they could easily help the community by rounding up their change when they were at the cash register checking out. In very little time, we had over $75,000 donated from our community, and the donations were distributed throughout local organizations supporting our displaced community members.

The other way we were able to help get resources back to the fire victims was through our new Round Up Program called Change for Good. We quickly communicated to our community about the need to support displaced families and how they could easily help the community by rounding up their change when they were at the cash register checking out. In very little time, we had over $75,000 donated from our community, and the donations were distributed throughout local organizations supporting our displaced community members.