“Happiness is having a large, caring, close-knit family in another city.” —George Burns

I love reading other happiness researchers’ findings, and this article by Paula Davis-Laack resonates with me. While you are reading it, think about how it relates to you. What’s true, and what’s not? What else is there for you? I am curious!

To illustrate this post, I’m using a photo of me with a few of my “tribe.” This was taken during our first evening together after starting a fast-track coaches training program at CTI last March. Love them!

Thanks to my friend Anne Golden for forwarding this to me. References follow.

Here we go!

How happy are you and why? This is a question I spend a fair amount of time thinking about, not only as it applies to my own levels of happiness, but also as it applies to my family, friends, and the people who I work with. Since graduating with my master’s degree in positive psychology, I’ve worked with and observed thousands of people in a wide variety of settings, and happy people just flow with the groove of life in a unique way. Here is what they do differently:

They build a strong social fabric. Happy people stay connected to their families, neighbors, places of worship, and communities. These strong connections act as a buffer to depression and create strong, meaningful connections. The rate of depression has increased dramatically in the last 50 to 75 years. The World Health Organization predicts that by 2020, depression will be the second leading cause of mortality in the world, impacting nearly one-third of all adults. While several forces are likely behind this increase, one of the most important factors may be the disconnection from people and their families and communities.

They engage in activities that fit their strengths, values, and lifestyle. One size does not fit all when it comes to happiness strategies. You tailor your workout to your specific fitness goals—happy people do the same thing with their emotional goals. Some strategies that are known to promote happiness are just too corny for me, but the ones that work best allow me to practice acts of kindness, express gratitude, and become fully engaged. Dr. Sonja Lyubomirsky offers a wonderful “Person-Activity Fit Diagnostic” in her book The How of Happiness.

They practice gratitude. Gratitude does the body good. It helps you cope with trauma and stress, increases self-worth and self-esteem when you realize how much you’ve accomplished, and often helps dissolve negative emotions. Research also suggests that the character strength of gratitude is a fairly strong correlate with life satisfaction.[1]

They have an optimistic thinking style. Happy people rein in their pessimistic thinking in three ways. First, they focus their time and energy on where they have control. They know when to move on if certain strategies aren’t working or if they don’t have control in a specific area. Second, they know that “this too shall pass.” Happy people “embrace the suck” and understand that while the ride might be bumpy at times, it won’t last forever. Finally, happy people are good at compartmentalizing. They don’t let an adversity in one area of their life seep over into other areas of their life.

They know it’s good to do good. Happy people help others by volunteering their time. Research shows a strong association between helping behavior and well-being, health, and longevity. Acts of kindness help you feel good about yourself and others, and the resulting positive emotions enhance your psychological and physical resilience. One study followed five women who had multiple sclerosis over a three-year period of time.[2] These women volunteered as peer supporters for 67 other MS patients. The results showed that the five peer support volunteers experienced positive changes that were larger than the benefits shown by the patients they supported.

They know that material wealth is only a very small part of the equation. Happy people have a healthy perspective about how much joy material possessions will bring. In The How of Happiness, Lyubomirsky explains that in 1940, Americans reported being “very happy” with an average score of 7.5 out of 10.[3] Fast forward to today, and with all of our iPods, color TVs, computers, fast cars, and an income that has more than doubled, what do you think our average happiness score is today? It’s 7.2. Not only does materialism not bring happiness, it’s a strong predictor of unhappiness. One study examined the attitudes of 12,000 freshman when they were eighteen, then measured their life satisfaction at age 37. Those who had expressed materialistic aspirations as freshmen were less satisfied with their lives two decades later.[4]

They develop healthy coping strategies. Happy people encounter stressful life adversities, but they have developed successful coping strategies. Post-traumatic growth is the positive personal changes that result from an individual’s struggle to deal with highly challenging life events, and it occurs in a wide range of people facing a wide variety of challenging circumstances. According to researchers Tedeschi and Calhoun, there are five factors or areas of growth after a challenging event: renewed appreciation for life, recognizing new paths for your life, enhanced personal strength, improved relationships with others, and spiritual growth. Happy people become skilled at seeing the good that might come from challenging times.

They focus on health. Happy people take care of their mind and body and manage their stress. Focusing on your health, though, doesn’t just mean exercising. Happy people actually act like happy people. They smile, are engaged, and bring an optimal level of energy and enthusiasm to what they do.

They cultivate spiritual emotions. According to Lyubomirsky, there is a growing body of science suggesting that religious people are happier, healthier, and recover more quickly from trauma than nonreligious people.[5] In addition, authors Ed Diener and Robert Biswas-Diener explain in their book Happiness: Unlocking the Mysteries of Psychological Wealth that spiritual emotions are essential to psychological wealth and happiness because they help us connect to something larger than ourselves.

They have direction. Working toward meaningful life goals is one of the most important strategies happy people utilize. I downplayed the importance of meaning during my law practice, but it became evident how much meaning mattered in my life when I burned out. Happy people have values that they care about and outcomes that are worth working for, according to Diener and Biswas-Diener.

The late, great Dr. Chris Peterson talked about his own journey with happiness as follows: “I spent my young adult years postponing many of the small things that I knew would make me happy … I was fortunate enough to realize that I would never have the time unless I made the time. And then the rest of my life began.”

Happy people have developed a specific set of strategies over time that causes them to see life differently—a balanced portfolio of skills and emotions. What would you add to this list?

(Tell me what YOU do! I’ll do the same.)

Paula Davis-Laack, JD, MAPP, is an internationally known writer and stress and resilience expert who helps high-achievers manage stress and increase well-being by mastering a set of skills proven to enhance resilience, build mental toughness and promote strong relationships.

References

[1] Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M.E.P. (2004). “Strengths of character and well-being.”

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619.

[2] Schwarz, C.E., & Sendor, M. (1999). “Helping others help oneself: Response shift effects in peer support.”

Social Science and Medicine, 48, 1563–75.

[3] Lane, R.E. (2000).

The loss of happiness in market democracies. New Haven: Yale University Press. See Figure 1.1, p.5.

[4] Nickerson, C., Schwartz, N., Diener, E., & Kahneman, D. (2003). “Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success.”

Psychological Science, 14, 531–36.

[5] Ellison, C.G., & Levin, J.S. (1998). “The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions.”

Health Education and Behavior, 25, 700–20.

Why not start the year with an empty jar and fill it with notes about good things that happen—as they happen? Then on New Year’s Eve, empty the jar and recall the year’s best moments.

Why not start the year with an empty jar and fill it with notes about good things that happen—as they happen? Then on New Year’s Eve, empty the jar and recall the year’s best moments. I was reminded of the classic book yesterday while Skyping with a young manager who trains employees for a multinational Fortune 100 consumer electronics firm in the Washington, D.C., area. She asked me if I’d ever read the book—well yes! We laughed. In 1982 when it was first published!

I was reminded of the classic book yesterday while Skyping with a young manager who trains employees for a multinational Fortune 100 consumer electronics firm in the Washington, D.C., area. She asked me if I’d ever read the book—well yes! We laughed. In 1982 when it was first published!

Springtime. Are you ready to emerge from your wintertime way of life and welcome the new possibilities of spring? I say, “Yes, I am” and when I look at what I’m doing, it’s perfect! Last month I began the fast-track co-active coaches training program at

Springtime. Are you ready to emerge from your wintertime way of life and welcome the new possibilities of spring? I say, “Yes, I am” and when I look at what I’m doing, it’s perfect! Last month I began the fast-track co-active coaches training program at  Fools, showers and tax returns. Perhaps T.S. Eliot was right when he wrote that “April is the cruelest month.”

Fools, showers and tax returns. Perhaps T.S. Eliot was right when he wrote that “April is the cruelest month.”

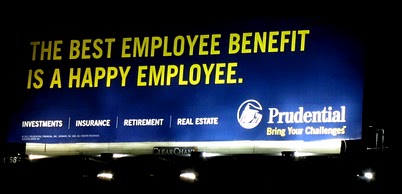

Happiness at work is a big topic these days. I spoke to a packed room at the Medford Rotary about it just last week. Even with unemployment still looming large, most people are carrying 150% or more of the workload they were hired for. Companies are cutting their workforce without lowering the expected output. Someone needs to pick up the slack. How can employees stay positive and how can a company justify investing in workforce engagement programs?

Happiness at work is a big topic these days. I spoke to a packed room at the Medford Rotary about it just last week. Even with unemployment still looming large, most people are carrying 150% or more of the workload they were hired for. Companies are cutting their workforce without lowering the expected output. Someone needs to pick up the slack. How can employees stay positive and how can a company justify investing in workforce engagement programs?

The Science Behind the Smile: Researchers are now measuring happiness and defining what really makes people happy. It’s not what you think. Yes, people who are rich, in a good relationship, actively participating in their church and healthy are happier overall. But events like getting a promotion, a new house or car or acing an exam only create more happiness for about three months. The frequency of positive experiences is more important than the intensity. And at work, what really contributes most to happiness is feeling appropriately challenged—when you’re striving to achieve goals that are ambitious but not out of reach. Managers take note: happier workers are more productive and creative. Years of research on rewards and punishment present a very clear finding: rewards work better.

The Science Behind the Smile: Researchers are now measuring happiness and defining what really makes people happy. It’s not what you think. Yes, people who are rich, in a good relationship, actively participating in their church and healthy are happier overall. But events like getting a promotion, a new house or car or acing an exam only create more happiness for about three months. The frequency of positive experiences is more important than the intensity. And at work, what really contributes most to happiness is feeling appropriately challenged—when you’re striving to achieve goals that are ambitious but not out of reach. Managers take note: happier workers are more productive and creative. Years of research on rewards and punishment present a very clear finding: rewards work better.